Subjectivity begs the question of sources.

Read MoreSocial contexts of art

What is Black Art? /

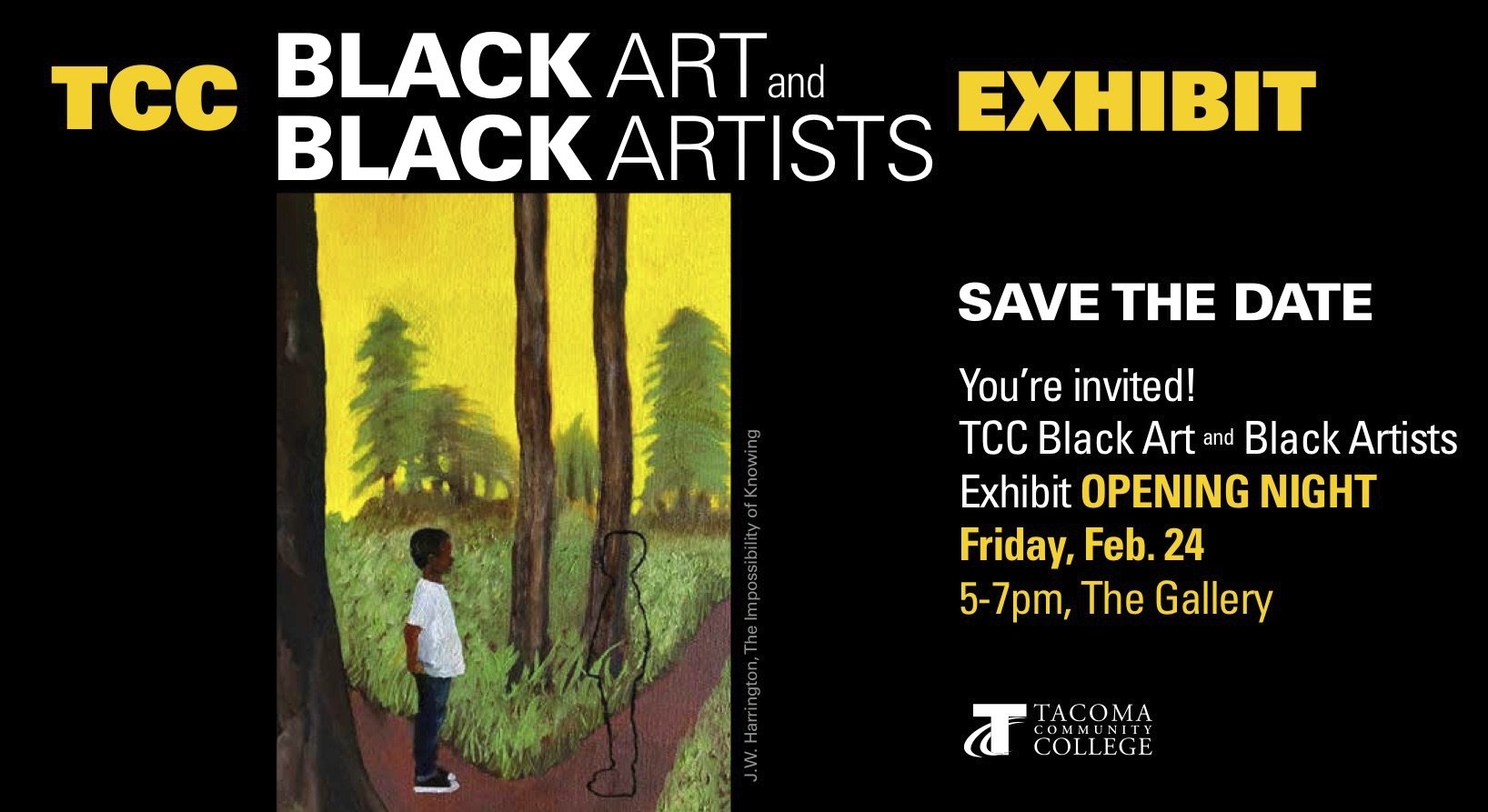

Friday 24 February brought together a tremendous gathering of artists, educators, and civic leaders for the opening of the Black Art and Black Artists exhibit at the Tacoma Community College Gallery. The exhibit runs through 17 March, open M-F, 10-5.

What is “black art”? I’ve been pondering that, since before I started painting. My most fundamental answer is “creative work that results from the African diaspora.” Simple words, but not straightforward.

For a few centuries, and especially in the US since the beginning of the twentieth century, the phrase “black art” in visual arts has implied some kind of social realism, using representation to depict the struggles and successes of Black people. For me and other abstract artists, this poses a conundrum.

We can easily circumvent the conundrum by declaring black art to be any creative work produced by a member of the African diaspora, whatever the medium and style – orchestral music, abstract poetry, abstract painting or sculpture. A diaspora is exactly that – a spreading of people across a wide geographic and cultural territory, resulting in a myriad of experiences and expressions.

Can a nonblack artist produce “black art”? Just last week, at the opening reception for the TCC Gallery show, my very thoughtful colleague Travis Johnson declared that the answer is “yes,” if the art reflects the culture and experiences of the African diaspora. Contemporary white artists produce hip-hop art that reflects African-American-rooted culture. Many composers and musicians have added to the jazz world of the twentieth century and beyond.

So I’ll return to that fundamental answer I gave above.

Let's try that again... /

This joyous image is from exactly a year ago, when I had completed all commitments of my professorial life and officially retired.

What an exciting moment! I faced that milestone with optimism, despite the horrors of COVID-19, murders at the hands of those who protect some and accost others, and daily (no, hourly — remember?) assaults on democratic institutions. I tried to portray that clash of personal and public circumstances by mimicking the colors above in a painting titled Superimposition: Retiring the Purple and Gold.

As planned, I returned to the (virtual) classroom this Spring — a way of “phasing” my retirement. TODAY, that phase is over. Most people I know are successfully vaccinated, and I’ve seen people in person! A few state-sanctioned murderers have been called out. We have at least a temporary reprieve from hourly, widely publicized assaults on political decency. I’m ready to try this retirement status again, in a new context:

(Cross) cultural appropriation in the arts, 4 /

Think about this, though: cultural appropriation, which is indeed a basis for much art, is a problem when it reduces the ability of some artists to get their (perhaps more authentic) work before and accepted by the broader public. Quoting Lauren Michelle Jackson’s brief article “When We Talk About Cultural Appropriation, We Should Be Talking About Power”:

[Most] discussions about appropriation have been limited to debates about freedom and choice, when [we] should be [dissecting] power. The act of cultural transport is not in itself an ethical dilemma. Appropriation can often be a means of social and political repair…. And yet. When the powerful appropriate from the oppressed, society’s imbalances are exacerbated and inequalities prolonged.

Art production should certainly celebrate and question the influences on the artist: how could it not? However, when the borrowing is from – and especially in – the voices, images, or styles of others, those others and their paths need to be acknowledged in ways that lead the listener, viewer, or reader to seek their work and their stories.